The Accidental Bookseller

Specializing in Uncommon Copies of Interesting Books

Membership(s): IOBA, FABA

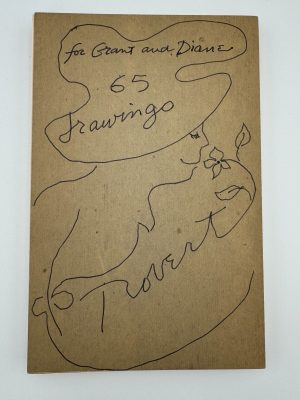

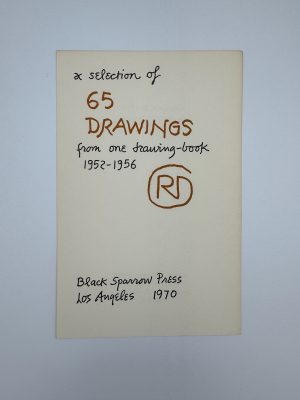

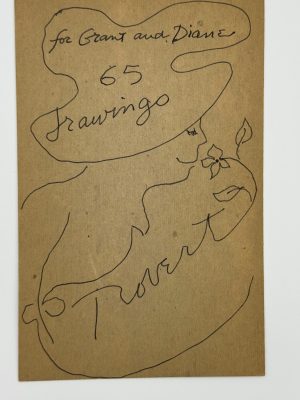

Duncan, Robert

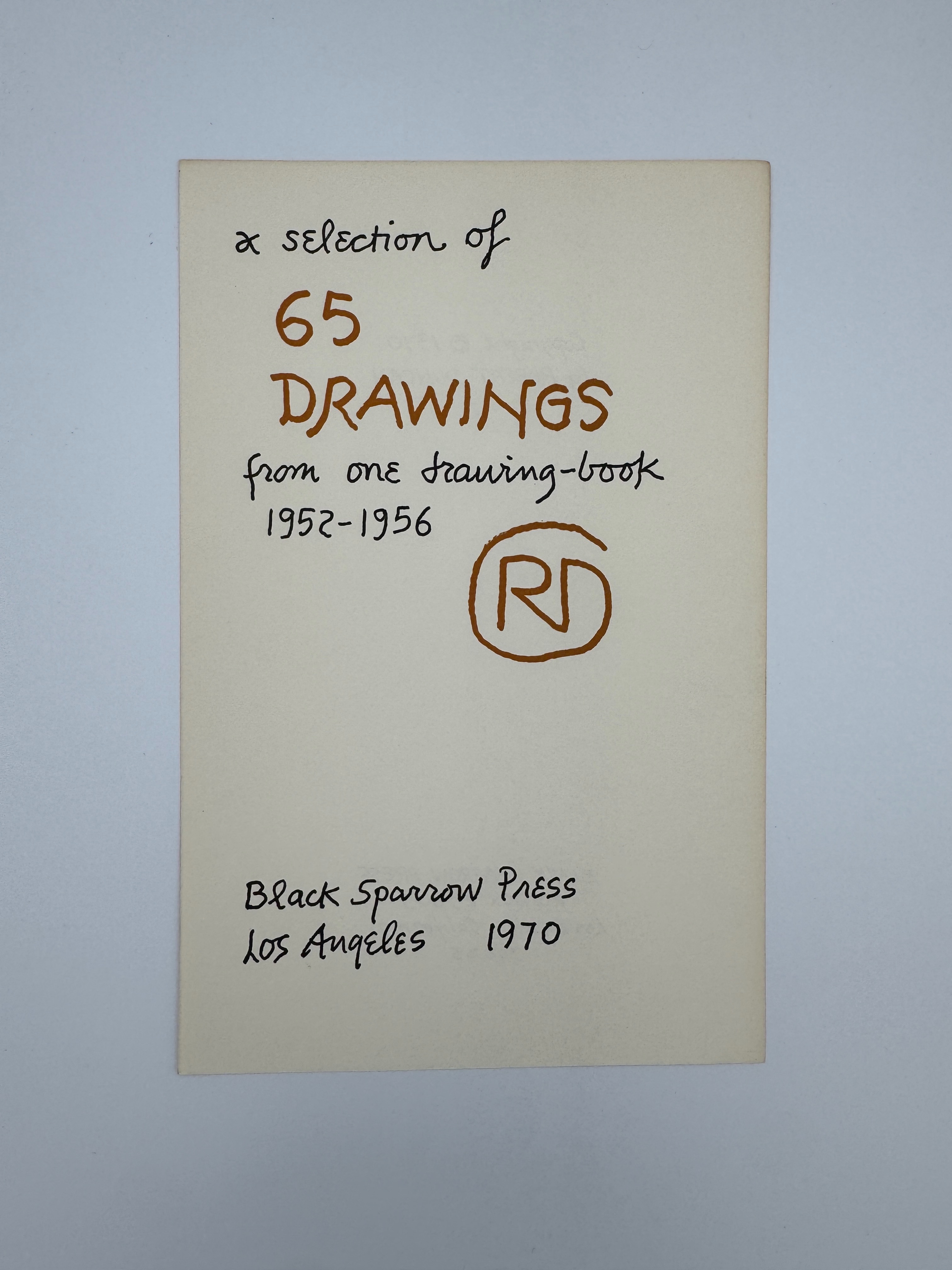

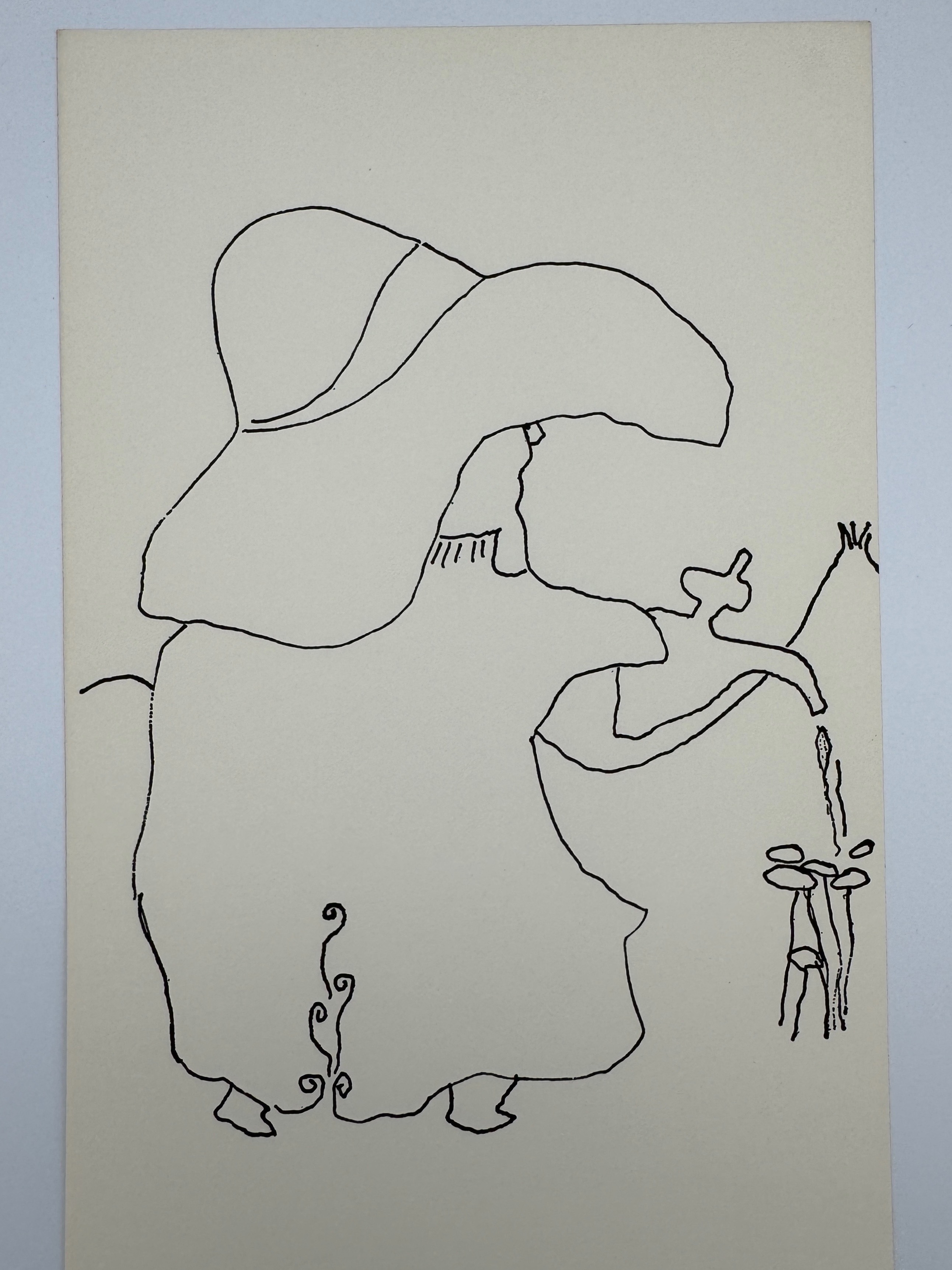

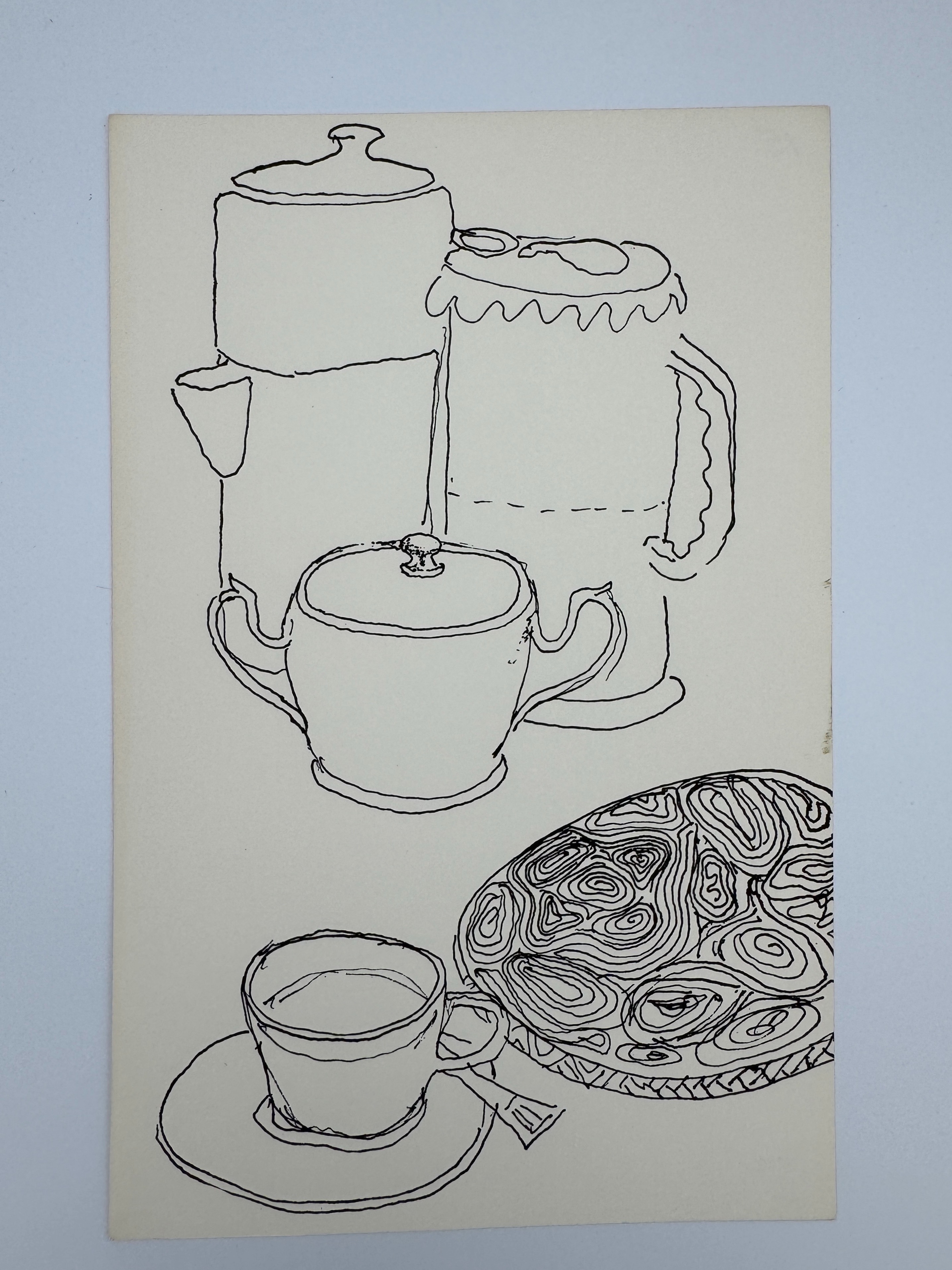

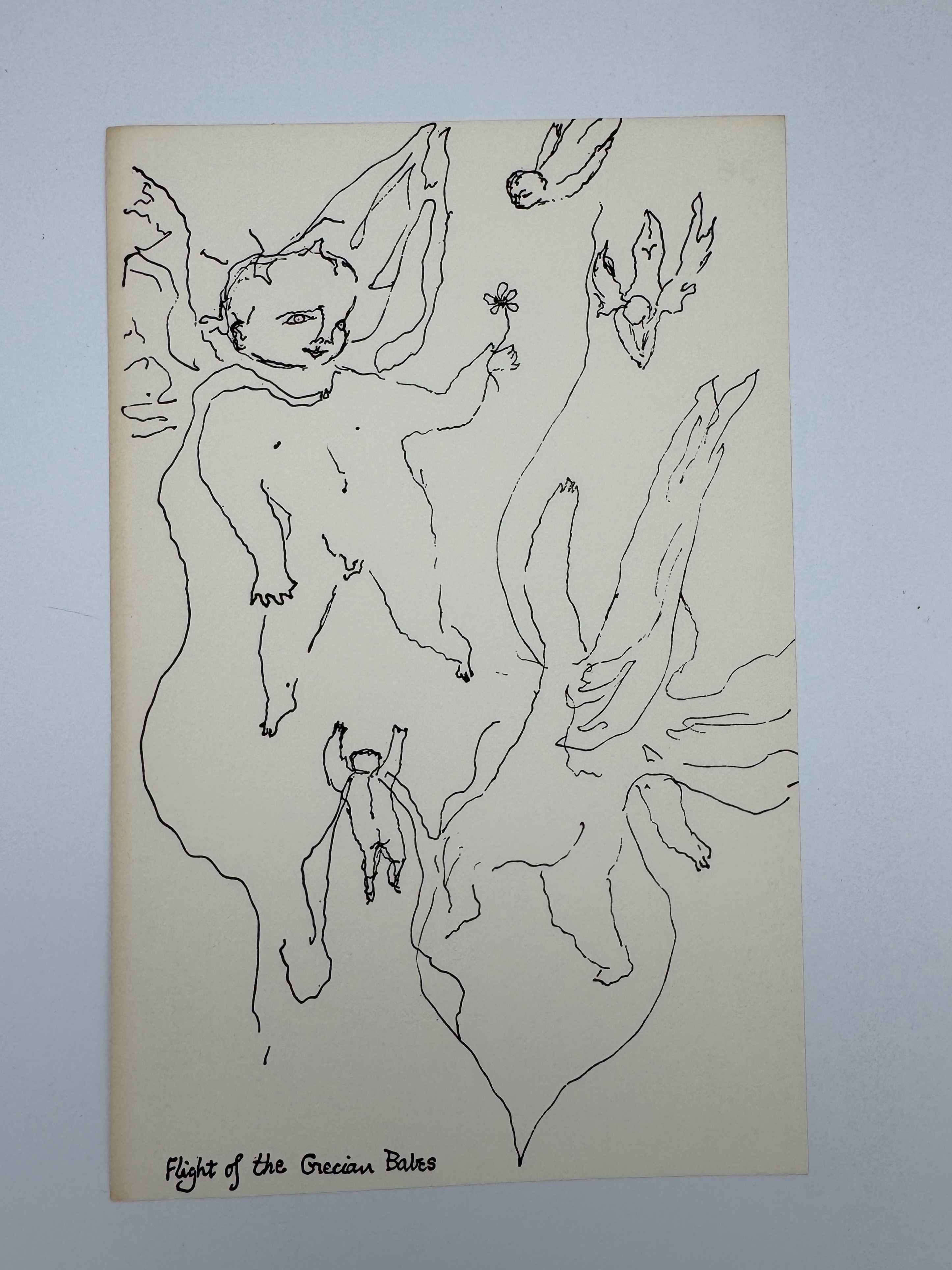

A Selection of 65 Drawings from one drawing book 1952-1956

$400.00

Duncan, Robert

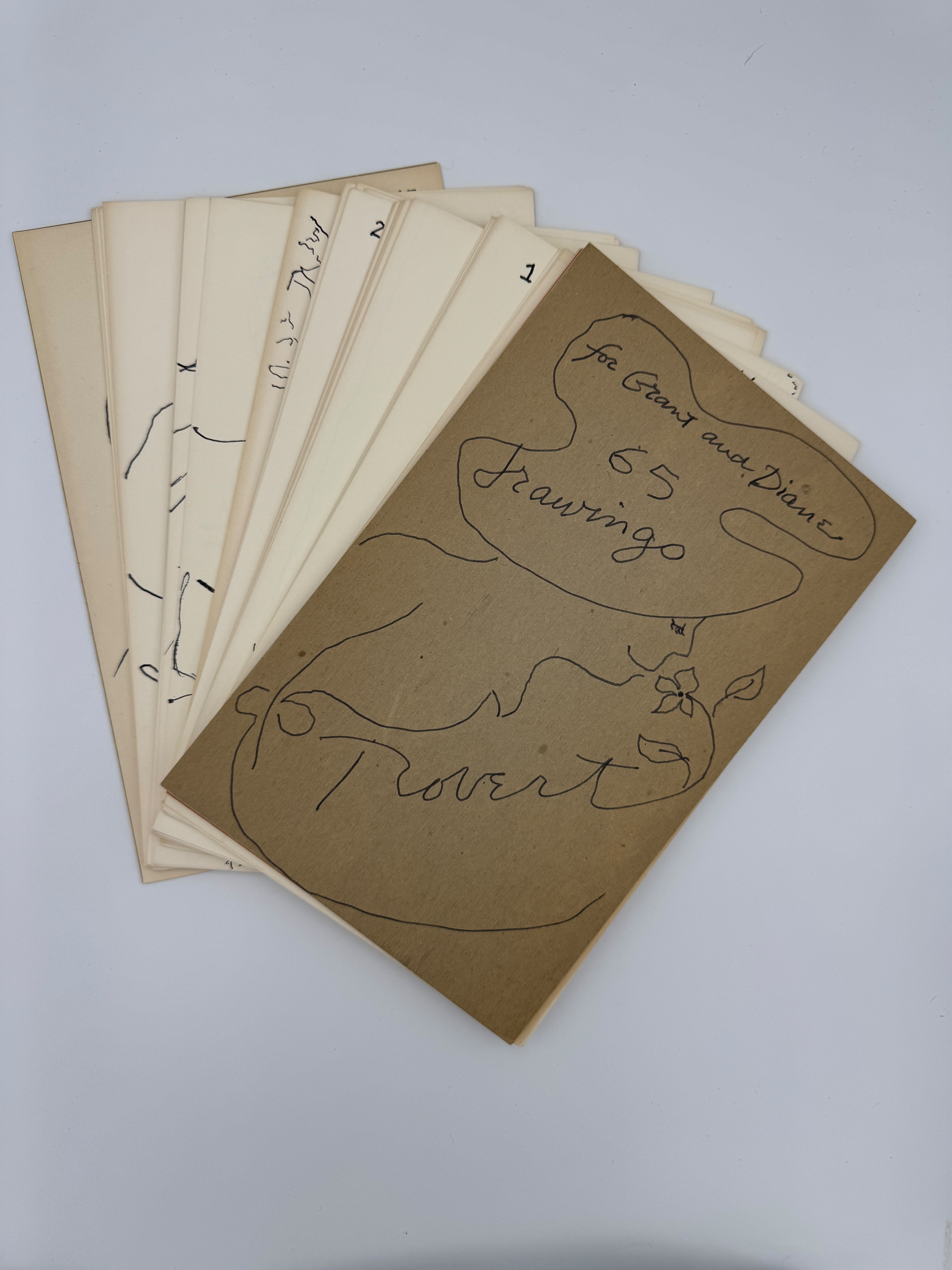

Black Sparrow Press: Los Angeles, 1970. 65 loose prints, not bound (as issued).

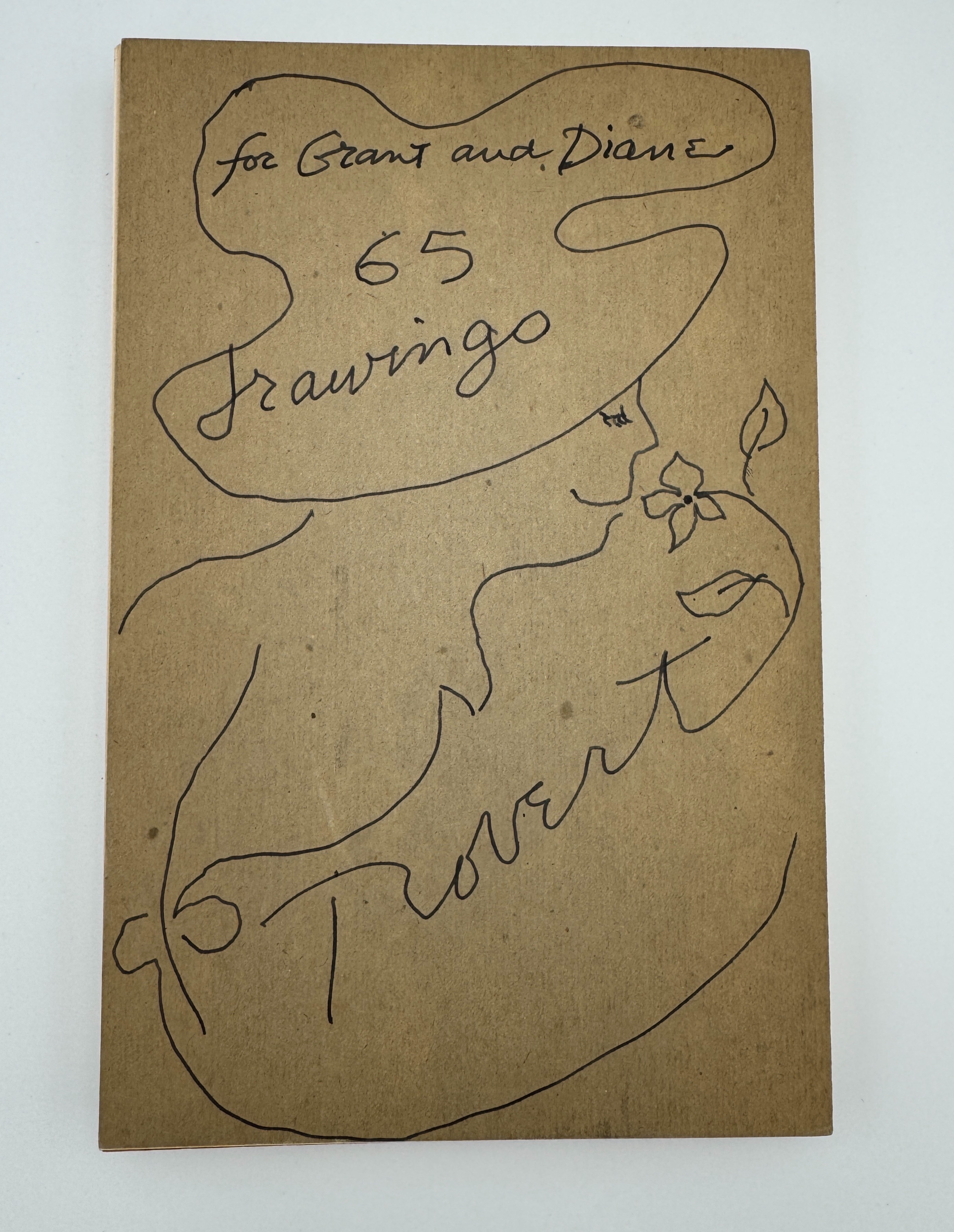

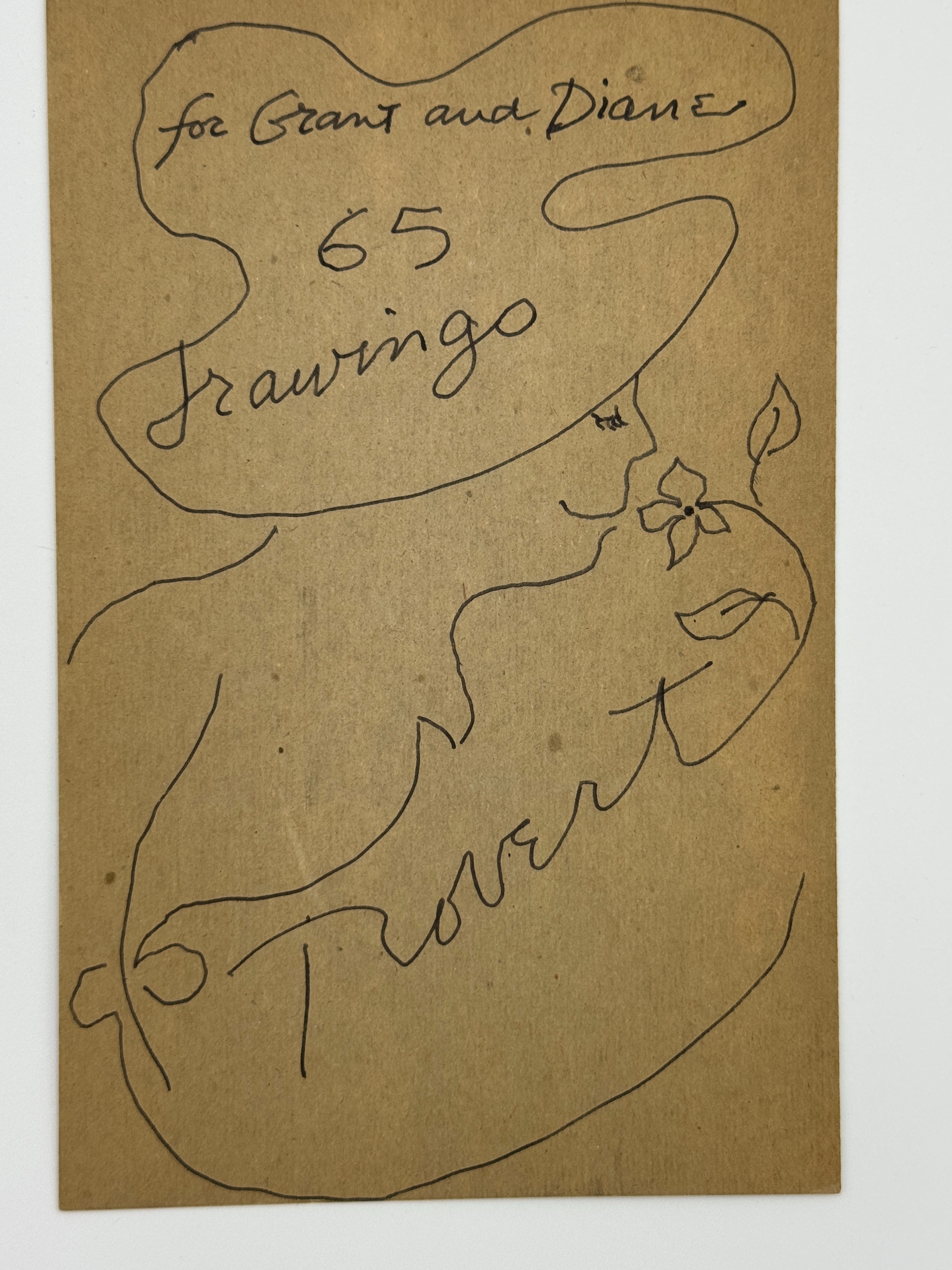

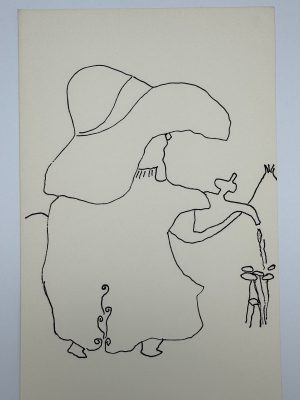

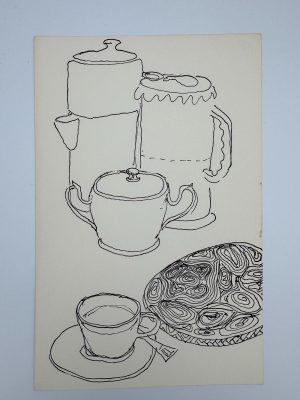

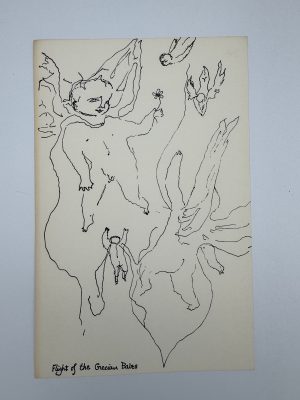

A signed presentation copy from Duncan to Diane di Prima and her second husband Grant (Fisher), with a full page original drawing on card stock, measuring 6″ X 9″, in the style of drawings from the book. The Black Sparrow Press item appeared with a publisher’s chemise and signed colophon page — these are not present here and presumably weren’t included in the author’s copies of the book.

A few minor age spots to card stock, otherwise fine.

When speaking of the impact of Duncan’s teachings, di Prima cited the lesson that poetry intensifies life. In an interview with fellow Beat poet David Meltzer, she recalled, “Robert was probably one of the closest, most intimate lovers I ever had, even though we never had a physical relationship. I learned a lot of different kinds of things from him. One of the things I learned—in a way no teacher of Buddhism ever showed me—was how precious my life was. How precious the whole ambience of the time. A real sense of appreciating every minute.”

di Prima recalled their personal relationship in an August 2001 interview with poet David Hadbawnik: “Robert used to come and hang for days, he’d move into my house in Marshall in the ’70s, and bring his French mysteries that he was teaching himself idiomatic French from, and his notebook, and he’d stay for days. And he always came to Christmases with the kids, because Jess doesn’t like holidays, and so I’d have to say mid-’70s, through ’75 on, he was there many weekends, many mornings…. Eating fried herring from the bay for breakfast.”

Related products

-

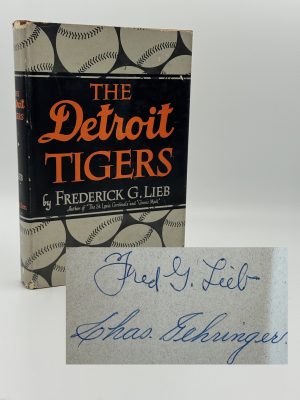

(Gehringer, Charles) Lieb, Fredrick G.

The Detroit Tigers

$400.00G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York (1946). Presumed first edition (no other printings indicated). Part of the “Putnam Sports Series”. Signed by the author, a Hall of Fame sportswriter inducted into Cooperstown in 1973. Also signed by Charles (“Chas”) Gehringer, Hall of Fame Tigers second baseman from 1924 – 1942. A lifetime .320 hitter with over 2,800 hits, Gehringer was one of the best fielding second baseman in the history of the game. At the time of his retirement, he owned the MLB record for double plays turned by a second baseman and remains among the all-time MLB leaders in assists and putouts. Lieb spent nearly 70 years as a sportswriter and is credited with coining the term “The House that Ruth Built,” referring to the New York Yankees’ brand new stadium. Over his career, he covered every World Series game from 1911 to 1958, 30 All-Star games, and over 8,000 major-league baseball games. Newsprint offset front pastedown and free end paper, little toning to rear free end paper, unobtrusive mark to front board, otherwise a bright, fresh and nearly fine copy in very good dust wrapper, corners clipped, slightly chipped at spine ends, rubbed along sides spine. less

moreOffered for Sale by: The Accidental Bookseller -

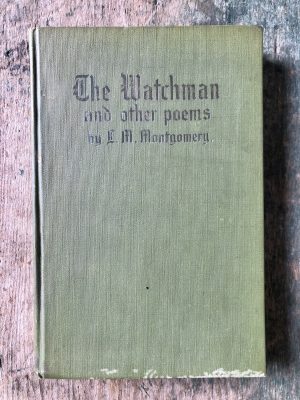

L. M. Montgomery

The Watchman and Other Poems

$600.00Under The Covers Antique And Vintage Books

Toronto; McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, [1916]. SCARCE. FIRST EDITION. 8vo. Hardcover. Very good. Green cloth covered boards with gilt title to front board and to spine. Fading to gilt. Minor fading to top edges of boards and to spine. Spots of discoloration to bottom edge of front board, spine, and top edge of rear board. Light soiling to rear board. Foxing to end papers, first and last few pages, and edges of text block. Text remains clean and bright. Un-trimmed edges with many pages unopened. Binding tight. The only book of poetry by Lucy Maud Montgomery. 159 pages. less

moreOffered for Sale by: Under The Covers Antique And Vintage Books -

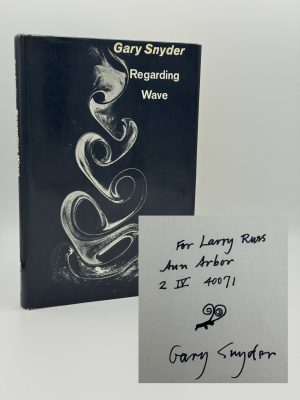

Snyder, Gary

Regarding Wave

$350.00New Directions: New York, 1970. First edition. Signed, located and dated in the year following publication, inscribed to the leader of the student-run Writer in Residence program at University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. Snyder has also added an original drawing of a small animal. Offsetting from laid in newsprint to title and opposite page, scant edgewear to spine tips, small spot top front board, otherwise a fine, tight and unread copy in fine, priced dust wrapper. A very fresh copy. less

moreOffered for Sale by: The Accidental Bookseller -

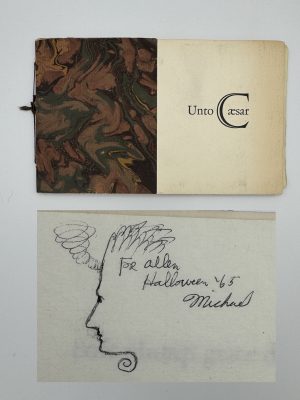

McClure, Michael

Unto Caesar

$450.00(San Francisco): (Dave Haselwood), (1965). A non-commercial publication, with most copies given away to friends of the author and printer. Hand-sewn in printed wrappers, 6.5″ x 4″, 24 pages, circa 60 copies. The first publication from Dave Haselwood after he left Auerhahn Press in the hands of his partner, Andrew Hoyem. This copy inscribed “For Allen”, signed “Michael”, and dated Halloween, 1965. Additionally, McClure has added a self-portrait drawing. Although not definitively established, it seems likely that the recipient is Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg and McClure both lived in San Francisco at the time, and the famous photograph of them with Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson in the alley behind City Lights Books was taken shortly after the date of the inscription. A very good copy, front wrap unevenly and lightly tanned, rear wrap with one light crease, spine a little rubbed, some interior pages don’t quite align to wraps (potentially as issued). less

moreOffered for Sale by: The Accidental Bookseller

USD

USD GBP

GBP EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD ZAR

ZAR